The Bikernieki race track lies not far from the center of Riga, Latvia’s capital. Tucked between a swarm of Soviet buildings and an idyllic forest, the one-mile loop is the crown jewel of the race complex. The Riga Motor Museum, which overlooks the course, is less well-known. Home to many wonderful machines, its centerpiece is an Auto Union Type C/D. The museum is literally built around the silver bullet. The hill-climber rests on an aluminum platform hanging from the ceiling of the main hall. It is an impressive sight, made more so by the story of how it ended up there.

Following the fall of the Nazi regime at the end of World War II, Soviet leaders ordered the KGB on a special mission. The goal: empty Horch’s Zwickau factory of all of its technology, including over a dozen Auto Union race cars. The Soviet Union put the cars on a train, squishing them together like sardines to make room for other equipment. When they arrived in the U.S.S.R., they were distributed across several factories for research.

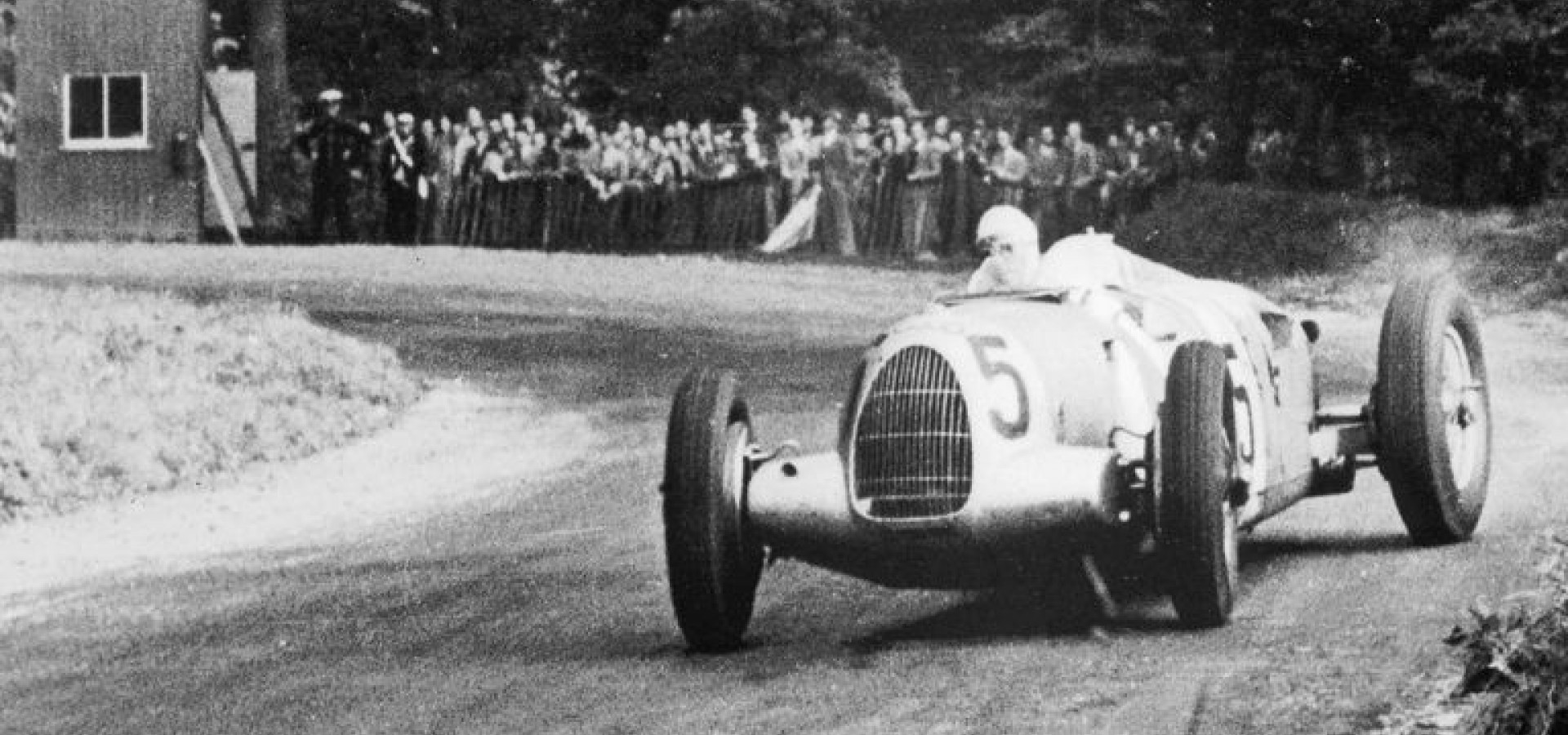

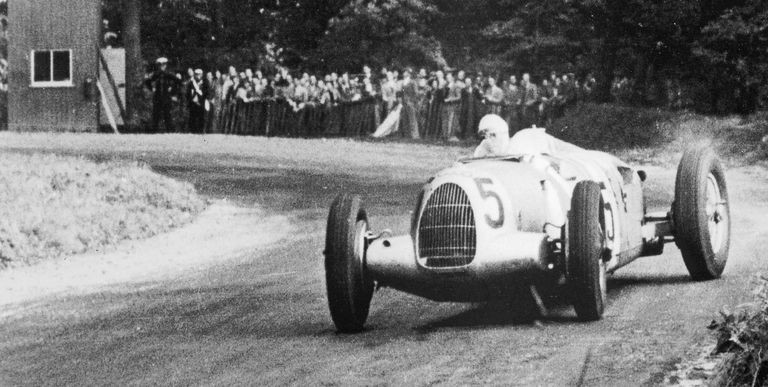

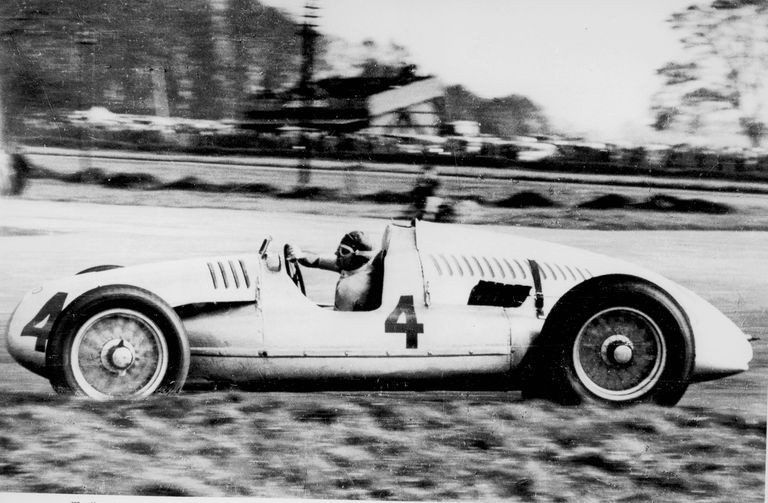

The Soviets quickly learned how difficult it was to control the Auto Union race cars. The state organized a demonstration on a highway nearby Moscow, where their war trophies could be paraded before a large crowd that had come to see the fabled machines. During the demonstration, disaster struck. The driver lost control, swerving off the road. The accident killed 19 people, 18 of them onlookers. With their bicycle tires, massive power, and incredible sensitivity, the Silver Arrows were only to be driven by the most gifted drivers. Men like Hans Stuck, Bernd Rosemeyer, and Tazio Nuvolari.

The accident was enough for the Soviet government to ban racing foreign cars altogether. And with that decision, there was virtually no incentive left for the Soviet Union to discover the many secrets of the silver racing machines. The country decided to lock them away to rot.

For a couple of decades, the cars were hidden where no one could find them. Eventually, orders were given to bring an end to the small collection of race cars. On the subbotnik in 1976, a day when workers had to ‘voluntarily’ clean up, plans were put in place for the racing wonders to meet their demise.

That’s when Viktors Kulberg, a Latvian, caught wind of the plans to destroy the racing cars. As president of the Antique Automobile Club of Latvia, Kulbergs used his contacts to try to persuade the Soviet rulers to let go of one remaining example, nicknamed the Bergrennwagen, a purpose-built hill climb racer. But the authorities turned down each and every one of Kulbergs’ offers, leaving him with nothing but to figure out a way to save the Auto Union Type C/D with only a couple of days to spare.

Of all the Auto Union Type-cars, the C/D-version might be the most interesting. This hill-climbing-variant, built by Dr. Robert Eberan von Eberhorst, was different from its brothers. While Grand Prix cars had to be made to conform to new engine rules, which spawned the Auto Union Type D, hill climbing cars had no such limits. Von Eberhorst dropped a, 520 horsepower, 6.0-liter, supercharged V-16 from the Type C into the Type D chassis.

Kulbergs knew all this, and he was not ready to give up. At the final hour, he launched a rescue operation, bribing an official from the ZIL-factory where the car had been sitting for decades. Together with some others, Kulbergs was able to save the Type C/D only eight hours before it was supposed to be scrapped.

When he was finally able to take a proper look at the car, Kulbergs realized the Auto Union was in a far worse condition than he thought. It was missing several key components after being neglected for three decades, and there was extensive body damage. But the automobile club took great pride in acquiring the car and decided to organize a special event the following year. In the meantime, the club did everything in its power to make the car look presentable. It also spent a significant amount of time and energy fabricating the missing parts so that it could drive at the event.

When the day finally arrived, Kulbergs sat behind the wheel with a smile as big as the country itself. After being dragged around the Biķernieki circuit with a rope in front of 70,000 spectators, Kulbergs decided to unhook and fire up the supercharged V-16, unleashing a roar that shook the crowd. Kulbergs drove the Auto Union for about a quarter mile before coming to a victorious stop.

It was a bright moment, but the story was far from over. When the world heard news that one of the Auto Unions had been saved from the Soviet Union, wealthy enthusiasts began approaching Latvia’s classic car club. They wanted the Type C/D for themselves. The club was offered everything from cash to a whole new building for their activities, but the club stuck to its guns and remained convinced the project would be a success, no matter how long the restoration took.

Fast forward 15 years, and the situation had changed. With the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the Iron Curtain and the Soviet Union, Latvia restored its independence after more than 70 years of Soviet rule. It was around that time that Kulbergs was approached by a party he could not ignore: the Volkswagen Auto Group. Unlike the others who’d tried to make off with the Type C/D, the automaker had another plan.

When the deal was struck, Volkswagen shipped the Type C/D to experienced British restorers in Sussex, Dick Crosthwaite and John Gardiner. Their namesake company, Crosthwaite & Gardiner Ltd., is a specialist in Auto Unions. The shop had already helped bring an Auto Union Type D back to its former glory. Using whatever original documents, photographs, and blueprints they could find, the shop rebuilt the Type C/D from the ground up, piece by piece, over the course of several months.

The now-completed project would, however, not be shipped back to Riga. Instead, the club would receive an exact replica of the Bergrennwagen. The original would be sent to the Audi Museum in Ingolstadt. The German marque made sure that the hill-climb version of the historic racer was nearly identical, from the steering wheel to the nuts and bolts. Upon arriving in Latvia, everything had been made ready for the replica to take its place, center stage, in the Riga Motor Museum – where it still resides more than 25 years later.

Although the Auto Union twin arrived in the museum a couple of years after it first opened in 1989, it was always intended to be its pièce de résistance. In fact, Kulbergs, who also took on the role of director, actually started the museum because he helped rescue the car. Today, the completely modernized interior is decorated with cars, motorcycles, and other vehicles.

As much of a present the identical twin of the original was, Audi decided to go out of its way to treat the man responsible for saving one of its very few remaining race cars from a bygone era. Aside from handing him the replica, Audi thanked Kulbergs for the great lengths he went through to save the Auto Union by granting him Latvia’s very first official Audi dealership and making him importer of the famous German marque.

Kulbergs remained a major shareholder in the company for over a decade, before taking up roles as president of the Latvian Chamber of Commerce and chairman of the board of the country’s automotive dealerships. Kulbergs passed away in 2013 at the age of 65, leaving behind an impressive empire along with the ever-lasting memory of his great rescue.

Original article BY MAR 27, 2020 re-published from R&T web page.

History video from CSDD web page: Auto Union V16 C/D